Sommaire

HISTOIRE - SOMMAIRE

France : Azincourt

France : Azincourt Family Chronicle

France : Le Pont d'Ouve - fortification in lancastrian normandy

France : Dives - Compagnons de Guillume le Conquérant

France : Tapisserie de Bayeux

Australie : Journey to Sydney 1790

Canada : Colonel Fortescue Duguid

Canada : Lawrence Fortesque

Etats-Unis :

G.B. : Companions of Duke William

G.B. - Domesday book

G.B. - Invasion of England, 1066

G.B. - Legend

G.B. - The Battle of Hastings

G.B. - The norman Invasion

G.B. - William the Conqueror

Indes : Analysis of the 1857 war of Independence

Australie - Journey to Sydney 1790

Australia's Second Fleet

A second fleet of six ships left England - Guardian, Justinian,

Lady Juliana, Surprize, Neptune, Scarborough. The Guardian struck

ice, and was unable to complete the voyage. She was stocked with

provisions. Only 48 people died in the first group of ships, but

this time 278 died during the voyage. This time transporting the

convicts was in the hands of private contractors.

_____________________________________________________

From the "SYDNEY COVE CHRONICLE", 30th June, 1790

At last the transports are here

DIABOLICAL CONDITION OF THE CONVICTS THEREON

278 died on the fearsome journey to Sydney Cove

-----" The landing of those who remained alive despite their

misuse upon the recent voyage, could not fail to horrify those

who watched.

As they came on shore, these wretched people were hardly able

to move hand or foot. Such as could not carry themselves upon

their legs, crawled upon all fours. Those, who, through their

afflictions, were not able to move, were thrown over the side of

the ships; as sacks of flour would be thrown, into the small

boats.

Some expired in the boats; others as they reached the shore.

Some fainted and were carried by those who fared better. More

had not the opportunity even to leave their ocean prisons for as

they came upon the decks, the fresh air only hastened their

demise.

A sight most outrageous to our eyes were the marks of leg irons

upon the convicts, some so deep that one could nigh on see the

bones. ----

----- We learn that several children have been borne to women

upon the Lady Juliana, the cause for which were the crews aboard

African slave ships which met up with the transport at Santa

Cruz.--- "

------" So the Guardian is lost and with it our provisions.

What, in the name of Heaven, is to become of us ? ----- "

A LIST OF THE CONVICTS WHO SET SAIL FROM OLD ENGLAND'S SHORES

Hereunder our Readers will find the names of convicts who were

to have sailed, or did sail, in the transports Neptune, Surprize,

Scarborough and Lady Juliana.

The information was compiled by our Correspondent in London and

is complete in so far as it lists all the convicts who were

recently landed upon our shores. It also, howso ever, gives the

names of convicts who, for various reasons of death &c., did not

travel with the Fleet to New South Wales. Unhappily, we find

ourselves at this time unable to indicate who sailed and who did

not.

We look to our Readers for their indulgence to involuntary

errors, though will find no omissions, and trust general

attention will secure us from trespassing on their kindness too

often.

NAME, Where Sentenced Term

...

FORTESCUE, William, Herts - - - - - - - - 7

...

Acknowlegement. Newspaper article transcribed in 1992 by Barbara Turner

The Sydney Cove Chronicle of 30 June 1790 is a fictitious newspaper which appeared as a four-page "composite newspaper" in the Sydney Daily Mirror on Monday 3 March 1969 . In the article which announced the publication, the Mirror stated that the newspaper, one of a series of two covering the Second and Third Fleets, was "written and compiled by Cirrel Greet, in the style of that time with the assistance of the Public Library of NSW and particularly its Archives Department" (now State Records (NSW)).

![]()

G.B. - Companions of Duke William

Companions of Duke William at Hastings

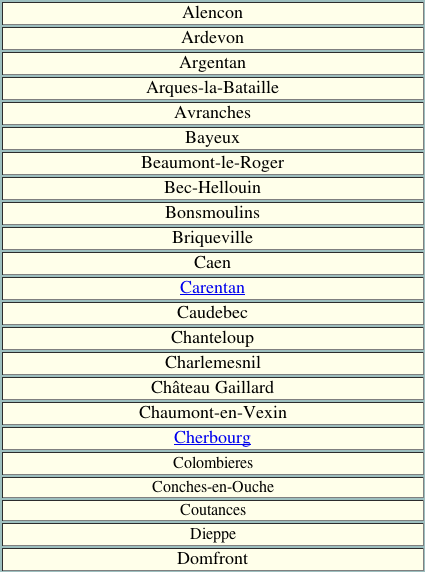

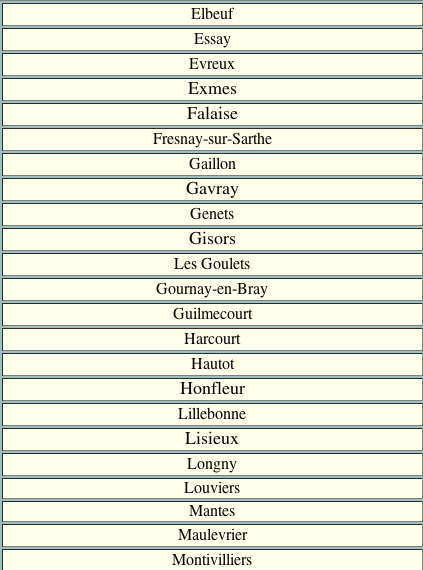

A combination of all the known Battell Abbey Rolls, including Wace, Dukes, Counts, Barons, Seigneurs who attended William at Hastings.

These were the commanders. They were the elite who had provided ships, horses, men and supplies for the venture. They were granted the Lordships.

The list does not include the estimated 12,000, Standard bearers, Men at Arms, Yeomen, Freemen and other ranks, although some of these were granted smaller parcels of England, some even as small as 1/8th of a knight's fee.

A

Ours d'Abbetot

Roger d'Abernon

Ruaud d'Adoube (Musard)

Engenoulf de l'Aigle

Richard de l'Aigle (de Aquila)

Herbert d'Aigneaux

Guatier d'Aincourt

Guillaume Alis

Guillaume d'Alre

Archard d'Ambrieres

Robert d'Amfreville

le Sire de Anisy

Guillaume d'Anneville

Guatier d'Appeville

Guillaume L'Archer

Norman D'Arcy

Arnoul d'Ardre

David d'Argentan

Le Sire d'Argouges

Robert d'Armentieres

Guillaume d'Arques

Osbern d'Arques

Bagod d'Arras

Roger Arundel

Geoffroi Ascelin

Hugh L'Asne

Gilbert d'Asnieres

Raoul d'Asnieres

Guillaume d'Aubigny

Le Sire d'Aubigny (Roger)

Guillaume d'Audrieu

Gilbert d'Aufay

Fouque Aunou

Le Sire d'Auvillers

Richard Vicomte d'Avranches

B

Guaillaume Bacon Sire de Molay

Le Sire de Bailleul

Guineboud de Balon

Hamelin de Balon

Robert Banastre

Osmond Basset

Raoul Basset

Robert Le Bastard

Endes, Eveque de Bayeux

Hugue de Beauchamp

Guillaume de Beaufou

Robert de Beaufou

Robert de Beaumont

Gautier du Bec

Geoffroi du Bec

Hugue de Bernieres

Guillaume Bertram

Robert Bertram, le Tort

Le Sire de Beville

Avenel des Biards

Richard de Bienfaite et d'Orbec

Guillaume Bigot

Robert Bigot, Seigneur de Maltot

Gilbert Le Blond

Robert Le Blond

Robert Blouet

Blundel

Honfroi de Boho

Hugue de Bolbec

Le Sire de Bolleville

Le Sire de Bonnesboq

Guillaume de Bosc

Le Sire de Bosc-Roard(Simon)

Raoul Botin

Eustach, Comte de Boulogne

Hugue Bourdet

Robert Bourdet

Herve de Bourges

Guillaume de Bourneville

Hugue de Bouteillier

Le Sir de Brabancon

Guillaume de Brai

Raoul de Branch

Le Seigneur de Brecey

Robert de Breherval

Brian de Bratagne, Comte de Vennes

Roger de Breteuil

Anvrai Le Breton

Gilbert de Bretteville

Dreu de La Beuvriere

Guillaume de Briouse

Adam de Brix

Guillaume de Brix

Le Sire de Brucourt

Robert de Buci

Serion de Burci

Michel de Bures

C

Guatier de Caen

Maurin de Caen

Guillaume de Cahaignes

Guillaume de Cailly

Le Sire de Canouville(Gautier)

Hugue Carbonnel

Honfroi de Carteret

Eudes, Comte de Champagne

Robert de Chandos

Guillaume Le Chievre

Le Sire de Cintheaux

Gonfroi de Cioches

Hamon de Clervaux

Le Sire de Clinchamps

Robert de Cognieres

Gilbert de Colleville

Guillaume de Colombieres

Geoffroi de Combray

Robert de Comines

Amfroi de Conde

Alric Le Coq

Guillaume Corbon

Hugue Corbon

Aubri de Couci

Roger de Courcelles

Richard de Courci

Robert de Courson

Geoffroi, Eveque de Coutances

Le Sire de Couvert

Gui de Craon

Gilbert Crispin

Guillaume Crispin

Mile Crispin

Hamon Le Seneschal, Sir de Crevecoeur

Robert de Crevecoeur

Ansger de Criquetot

Le Sire de Cussy

D

Roger Daniel

Rober le Despensoer

Henri de Domfront

Gautier de Douai

Le Sire de Driencourt

E

Richard de'Engagne

Le Sire d'Epinay

Etienne Erard

Le Sire d'Escalles

Auvrai d'Espagne

Herve d'Espagne

Raoul L'Estourni

Richard L'Estourni

Robert d'Estouteville

Robert Count d'Eu

Gautier Le Ewrus(Roumare or Rosmar)

Guillaume, Count d'Evreux

Roger d'Evreux

F

Alain Fergant, Count de Bratagne

Guillaume de Ferrieres

Mathieu de la Ferte Mace

Guatier Fitz Autier

Fitz Bertran de Peleit

Adam Fitz Durand

Robert Fitz Erneis

Alain Fitz Flaald

Guillaume Fitz Osberne

Robert Fitz Picot

Robert Fitz Richard

Toustain Fitz Rou

Eudes Fitz Sperwick

Guatier Le Flamand

Raoul de Fourneaux

Le Sire de Fribois

G

Le Sire de Gace

Raoul de Gael

Gilbert de Gand

Berenger Giffard

Gautier Giffard, Count de Longueville

Osberne Giffard

Le Sire de Glanville

Le Sire de Glos

Ascelin de Gournay

Hugh de Gournay

Guillaume de Gouvix

Anchetil de Gouvix

Hugue de Grentiemesnil

Robert de Grenville

Robert Guernon, Sire de Montifiquet

Hugue de Guidville

Geoffroi de la Guierche

H

Gautier Hachet

Eudes le Seneschal, Sir de la Hale

Errand de Harcourt

Herve de Helion

Hugue d'Hericy

Tithel de Heron

Robert Heuse

Hugue d'Houdetot

I

Jean d'Ivri

Roger d'Ivry

J

Le Sire de Jort

L

Guillaume de Lacelles,

Gautier de Lacy

Ibert de Lacy

Baudri de Limesi

Auvrai de Lincoln

Ingleram de Lions

Le Sire de Lithaire

Honfroi vis de Loup

Guilliame Louvet

M

Hugue de Macey

Durand Malet

Gilbert de Malet

Guillaume Malet de Graville

Robert Malet

Raoul de Malherle

Foucher de Maloure

Geoffroi de Mandeville

Guillaume de La Mare

Hugue de La Mare

Geoffroi Martel

de Mathan

Auvrai Maubenc

Guillaume Maubenc

Ansold de Maule

Guarin de Maule

Juhel de Mayenne

Adeldolf de Mert

Du Merle

Auvrai de Merleberge

Baudoin de Meules at du Sap

Guillaume de Monceaux

Ansger de Montaigu

Roger de Montbray

Gilbert de Montichet

hugue de Montfort le Connestable

Roger de Montgomerie

Robert Moreton

Roger Moreton

Geoffroi, Seigneur de Mortagne

Robert Count de Mortain

Hugue de Mortimer

Guillaume de Moulins, Sir de Falaise

Paisnel des Moutiers-Hubert

Guillaume des Moyon

Robert Murdac

Enisand Musard

De Muscamp

Roger de Mussegros

N

Bernard Neufmarche

Gilbert de Neuville

Richard de Neuville

Noel

Le Comte Alain Le Noir

Corbet Le Normand

O

Roger d'Oistreham

Le S ire de Orglande

Le Sire de Origny

Raoul de Ouilli

Robert d'Ouilli

P

Le Sire de Pacy

Raoul Painel

Guillaume de Pantoul

Guillaume Patry de Lande

Guillaume Peche

Guillaume de Percy

Guillaume Pevrel

Renouf Pevrel

Roger Picot

Anscoul de Picquigni

Giles de Picquigni

Guillaume de Picquigni

Geoffroi de Pierrepont

Robert de Pierrepont

Le Sire de Pins

Le Chevalier de Pirou

Le Sire de Poer

Thierri Pointel

Gautier lLe Poitevin

Roger de La Pommeraie

Hubert de Port

Hugue de Port

Le Sire de Praeres (Prous)

Eudes Dapifer, Sire de Preaux

R

Roger Rames

Sire de Rebercil

Guillaume de Reviers

Richard de Reviers

Geoffroi Ridel

Adani de Rie

Hubert de Rie

Hubert de Rie le Jeune

Raoul de Rie

Anquetil de Ros

Golsfrid de Ros

Guillaume de Ros

Serlon de Ros

Hugue de Rousel

Le comte Alain Le Roux

Turchil Le Rous

S

Guillaume,Le Sire de Rupierre

Richard de Saint Clair

Richard de Daint Jean

Robert de Saint Leger

Le Sire de Saint Martin

Guido Saint Maur

Bernard de Saint Ouen

Germond de Saint Ouen

Huge de Saint Quentin

Neel Vicomte de Saint Sauveur

Le Sire de Saint Sauver

Le Sire de Saint Sever

Bernard de St Valery

Gautier de Saint Valery

Osbern de Sassy

Raoul de Sassy

Guillaume de Saye

Picot de Saye

Guillaume de Semilly

Garnier de Senlis

Simon de Senlis

Richard de Sourdeval

T

Guillaume Taillebois

Ivo Taillebois

Raoul Taillebois

Taillefer

Geoffroi Talbot

Guillaume Talbot

Richard Talbot

Le Chamberlain de Tancarville

Raoul Tesson

Amaury, Vicomte de Thouars

Raoul de Tilly

Gilbert Tison

Robert de Todeni

Neel de Toeni

Raoul de Toeni

Le Sire de Touchet

Le Sire de Touques

Le Sire de Tourneur

Le Sire de Tourneville

Le Sire de Tournieres

Martin de Tours

Le Sire de Tracy

Le Sire de Tregos

Le Sire de Troussebot(Pagan)

V

Gui de la Val

Hamon de la Val

Guillaume de Valecherville

Ive de Vassy

Robert de Vassy

Guillaume de Vatteville

Ansfroi de Vaubadon

Renaud de Vautort

Aitard de Vaux

Robert de Vaux

Gilbert de Vanables

Raoul Le Veneur

De Venois

Aubri de Ver

Bertran de Verdun

Gautier de Vernon

Huard de Vernon

Richard de Vernon

Le Sire de Vesli

Hugue de Vesli

Mile de Vesli

Guillaume de Vieuxpont

Robert de Vieuxpont

Godefroi de Villers

Vital

Robert de Vilot

Andre de Vitrie

Robert de Vitrie

W

Wadard

Hugue de Wanci

Osberne de Wanci

Guillaume de Warren

© 1996 Hall of Names International Inc.

G.B. - The Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings

1066 and much more

A brief of the events that led to our great heritage.

Duke William of Normandy left St.Valery in Normandy with about 600 ships and 10-12,000 men on Sept 27th in 1066.

William and his barons had been recruiting and preparing the invasion of England since early spring of that year. He was a seasoned general and master tactician, using cavalry, archers and infantry and had fought many notable battles. Off Beachy Head, his ship, the Mora, arrived ahead of the fleet.. William waited and ate a hearty breakfast. As his fleet straggled into place behind him they moved eastward to the first sheltered bay to provide protection for his armada. Pevensey and Bulverhythe were the villages on each promontory. Pevensey, to the west, was protected by an old Roman Fort and behind the fort there was much flat acreage to house his large Army. To suggest this landing was not pre-planned, is not in keeping with the preparatory time taken by William, or his track record. There had been much intelligence gathering in the past few months.

The bay, wide enough for maneuverability of this large fleet, was flat shored. William is said to have fallen on the beach, grasped the sand, and declared "This is my country" or words to that effect. Next, the ships were disembarked without resistance. They included 2,500 horses, prefabricated forts, and the materiel and equipment was prepared for any contingency. The ships shuttled in and out of the bay with the precision of a D Day landing. A Fort was built inside Pevensey Roman Fort as an H.Q, while the army camped behind it. William and FitzOsborn scouted the land He was unhappy with the terrain but it had proved to be a satisfactory landing beach. Taking his army around Pevensey Bay he camped 8 miles to the east, north of what is now known as Hastings all of which was most likely pre-planned. He camped to the east outside the friendly territory of the Norman Monks of Fecamp who may have been alerted and were waiting for his probable arrival. William waited. Perhaps he was waiting to know of the outcome of the battle to the north. In those two weeks William could have marched on London and taken it. He was obviously waiting for something?

Harold, far to the north in York at Stamford Bridge, was engaged in a life and death struggle against his brother who had teamed up with the Viking King Hadrada to invade England. Whether this was a planned Norman tactic, part of a pincer movement north and south, is not known, but students of Norman and Viking history might find it very feasible. The timing of each invasion was impeccable, and probably less than coincidental. Harold managed to resist the invasion to the north and killed both commanders. He was advised of the landing to the south by William.

Bringing the remnants of his Army south, Harold camped outside London at Waltham. For two weeks he gathered reinforcements, and exchanged taunts, threats and counterclaims to the Crown of England with William. Finally he moved his army south to a position about six miles north of where William waited.

Perhaps one of the most devastating events preceeding the battle was Harold's sudden awareness that he had been excommunicated by the Pope, and that William was wearing the papal ring. It is most likely this had been arranged by fellow Norman Robert Guiscard who had conquered most of southern Italy and was patron of the Pope who was indebted to him for saving the Vatican. Harold's spirit flagged. William was leading what might perhaps by called the first Crusade. The whole world was against Harold.

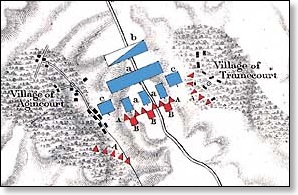

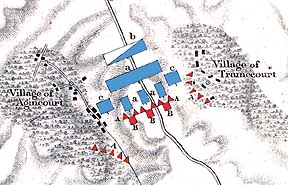

William moved up to Harold's position and set up in what was then the conventional European style. Archers, infantry and cavalry in the rear. A set piece, each assigned to their own duties. .

Harold waited. He and his brother Gyrth arranged a mass of men along a high ground ridge 8 deep, 800 yards long . A fixed corridor of tightly wedged humanity. Strategically, given the relative equipment of each side, it was hopeless from the start. To William it was almost a formality. Harold's men were hemmed in by their own elbows. William, with total mobility, held his Breton, Maine and Anjou contingents to the left of the line, the Normans the main thrust, the Flemish and French to his right. The flanking movements paid off. How long the battle took has varying estimates. Some say as little as two hours. Some as long as six hours. The latter seems more reasonable simply because of the numbers involved.

This battle would later be called Senlac, a river of blood. It demolished most of the remnants of the Saxon fighting men of the Island at very little cost to William.

It is very doubtful if Harold was shot in the eye with an arrow from over the ranks of his front line. He was probably run through by William's lance, accompanied by three others who were in at the kill, and who savaged him brutally.

Thus began a three century Norman occupation of England, Wales and Scotland, and later Ireland. It all started at Pevensey.

![]()

Indes - Analysis of the 1857 war of Independence

Chapter Two

The Causes Of The Rebellion

Maj (Retd) AGHA HUMAYUN AMIN from WASHINGTON DC gives a brilliant analysis of the 1857 war of Independence

The events of 1857 were unique both in terms of historical precedence and in terms of the socio-political sphere as far as India was concerned. India as a region has known foreign invaders more frequently than any other region in world history. The reason for it does not lie in the docility or weakness of the Indo-Pak people but in the peculiar geographical position of India by virtue of being bounded in the north by a vast inhospitable and unproductive region which starts from beyond the Indus valley and stretches far north into the steppes of central and eastern Asia. It is an irony of history that the east Asian tribes and races forced the west Asian nomads of Mongol and Turk origin to seek their barbaric design for plunder westwards and these central Asian people repeatedly invaded India. In the process these central and north east Asian nomadic people conquered and colonized China also but also extended their sway in South Asia as well as West Asia.

...

Sir Charles Napier, the Commander-in-Chief of Bengal Army was also convinced that the Bengal Army was the most serious threat to EEIC rule. In 1849 he wrote that it was apparent to him and to all officers on the spot who were conversant with Native and Sepoy habits and feelings, that a widely spread and formidable scheme of mutiny was in progress, and great danger impending 82.'

Whatever historians may state now a cursory glance at the situation in 1857 makes one thing very clear that without the Bengal Army there would have been no rebellion, but this is only one aspect. The other aspect is that without the Bengal Army or for that matter the Madras or the Bombay armies there would have been no EEIC's conquest of India. So the 'Bengal Army Factor' works both ways, it was instrumental in EEIC's success in the first place and it was instrumental in the rebellion also. But the Bengal Army's alienation was a slow process. Mutinies started right from 1757 but these were over administrative, financial and caste matters and not to overthrow EEIC's rule. The transition of rebellion or a bid for independence is always a slow and subtle process. It is in this regard that the British argument that 1857 was just a soldier's mutiny is baseless. The Bengal Army did fight for EEIC for hundred years but by 1857 it was no longer the force that it was in 1757. We will examine the salient aspects which brought this change of perception in the Bengal Sepoy :- (1) The prime motivation of the Bengal Army soldiers in joining the army was economic. Just like the Irishmen of 18th, 19th or 20th centuries. It is true that the British were masters in making other races fight their wars through a subtle system based on regimental pride, motivation, resolute leadership espirit de corps etc. But the essential fact was that the Bengal Sepoy was an Indian and a subject. It is true that the British treated their native soldiers much better than most native soldiers were treated by native rulers. But race is a very rigid barrier and is made more rigid by difference of religion. Man's basic needs are food, water and air, but once these are fulfilled he strives for higher needs and ideals like freedom and independence. The racial barrier which made it impossible for a native to ever be an officer was a major factor in producing alienation. (2) The Bengal Army was composed of 80% Hindu Brahman and Rajputs. Their daily rituals were complicated and conflicted with demands of military life. Slowly and steadily it increased their hatred of their officers and EEIC not because of any personal reason but simply because they belonged to an alien race who they perceived as bent upon damaging their religious sensitivities. Two aspects were important in this regard i.e. travel across sea which was regarded by the high caste Hindus and Rajputs of that time as something which would soil and pollute the purity of their caste. The second was going across the Indus westwards which again in their opinion polluted the purity of their caste. Thus once the First Afghan War started the Bengal Army was deployed west of Indus. This had a serious effect on the morale of the Hindu Brahmans for the reasons : (1) Once the Brahmans crossed the Indus their caste was rendered impure and on return to India they had to spend heavy sums of money on the rituals through which they had to undergo in order to be readmitted to their high caste83. (2) West of Indus they had to eat food which they considered impure and this also soiled their caste. (3) In Afghanistan due to cold climate the Hindus could not carry out the rituals of bathing etc. This was the major reason for the post 1841 rapid decline in the Hindu soldiers morale and not the initial reverses suffered in the First Afghan War. (4) The Muslim troops employed in the First Afghan war were demoralised because they were deployed after a long time against the Muslims. The last time they were deployed against a Muslim state was in 1774 during the Rohilla war. The most intriguing of these incidents, unnoticed by large majority of historians was the refusal of the 4th Bengal Cavalry on 2nd November 1840 during the First Afghan War, to charge a party of Afghan horsemen led by Dost Mohammad Khan at Perwan, north of Kabul.The British historian John Fortescue had no answer for the reason why the 2nd Bengal Light Cavalry fell back and fled from the battle field. Fortescue thus said about this incident that; 'And then followed one of those incidents which after endless explanation remain always mysterious. The 2nd Light Cavalry was a good corps with good officers; but such misconduct could not be overlooked and the regiment was with ignominy disbanded'84. The British did not understand why 2nd Light Cavalry had behaved like that. There was another likely explanation for this behaviour which had a deep connection with 2nd Light Cavalry's history. The 2nd Light Cavalry was raised from Afghans of Kandhari origin settled at Lucknow in 1788 by the Nawab Vizier of Oudh. It became the 2nd Bengal Light Cavalry only in 179685. It is possible that their peculiar Afghan origin may have played a part in their reluctance to charge the Afghans at Perwan!

...

But the introduction of the Greased Cartridges in 1857 was the final and decisive blow. These cartridges which the sepoys thought contained cow or swine's fat was a definite attack on the religion of both Hindus and Muslims. These cartridges gave a simultaneous common ground to both to rationalize their hatred of the EEIC European. The dispersion of British troops and their being outnumbered overwhelmingly in 1857 was the final blow. 'Petty parsimony on part of supreme government in matters of allowances provoked a number of small mutinies in 1843 and 1844.'88 This is the verdict of Sir John Fortescue, the official historian of the British army. Fortescue went further, he noted that 'the same cause amounting to positive injustice brought a number of Bengal Regiments to the verge of revolt in 1849'89. In this case, Sir Charles Napier the Commander-in-Chief of the Company's Bengal Army's confrontation and subsequent resignation was a decisive event. There were two mutinies in the two respective regiments of Bengal Army over stoppage of allowances. Sir Charles Napier disbanded one and restored the allowances for the second. Lord Dalhousie censured him and revoked his orders. Dalhousie was a civilian and a young man. He did not understand the demoralizing effect which this action had on the soldiers of Bengal Army. Sir Charles Napier resigned and went back to Britain in 185090. Sir John Fortescue's opinion on this episode is worth quoting, 'The sepoys thus saw the chief, who had observed equity on their behalf, rewarded by public disgrace'.91

...

Notes and References

43. Page-140 & 428-J.W Fortescue-Op Cit.

84. Page-138- A History of the British Army-Volume-XII-1839-1852-Hon J.W Fortescue-Macmillan and Company Limited, London-1927.

86. Page-230-J.W Fortescue-British Army-Volume-XII Op Cit.

88. Page 238- A History of the British Army-Volume-XIII-1852-1859- Hon J.W Fortescue-Macmillan and Co-London-1930.

91. Pages-234 to 238-J.W Fortescue-Vol-XIII-Op Cit.

![]()

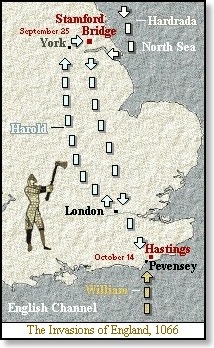

G.B. - Invasion of England, 1066

Invasion of England, 1066

King Edward of England (called "The Confessor" because of his construction of Westminster Abbey) died on January 5, 1066, after a reign of 23 years. Leaving no heirs, Edward's passing ignited a three-way rivalry for the crown that culminated in the Battle of Hastings and the destruction of the Anglo-Saxon rule of England.

The leading pretender was Harold Godwinson, the second most powerful man in England and an advisor to Edward. Harold and Edward became brothers-in-law when the king married Harold's sister. Harold's powerful position, his relationship to Edward and his esteem among his peers made him a logical successor to the throne. His claim was strengthened when the dying Edward supposedly uttered "Into Harold's hands I commit my Kingdom." With this kingly endorsement, the Witan (the council of royal advisors) unanimously selected Harold as King. His coronation took place the same day as Edward's burial. With the placing of the crown on his head, Harold's troubles began.

Across the English Channel, William, Duke of Normandy, also laid claim to the English throne. William justified his claim through his blood relationship with Edward (they were distant cousins) and by stating that some years earlier, Edward had designated him as his successor. To compound the issue, William asserted that the message in which Edward anointed him as the next King of England had been carried to him in 1064 by none other than Harold himself. In addition, (according to William) Harold had sworn on the relics of a martyred saint that he would support William's right to the throne. From William's perspective, when Harold donned the Crown he not only defied the wishes of Edward but had violated a sacred oath. He immediately prepared to invade England and destroy the upstart Harold. Harold's violation of his sacred oath enabled William to secure the support of the Pope who promptly excommunicated Harold, consigning him and his supporters to an eternity in Hell.

The third rival for the throne was Harald Hardrada, King of Norway. His justification was even more tenuous than William's. Hardrada ruled Norway jointly with his nephew Mangus until 1047 when Mangus conveniently died. Earlier (1042), Mangus had cut a deal with Harthacut the Danish ruler of England. Since neither ruler had a male heir, both promised their kingdom to the other in the event of his death. Harthacut died but Mangus was unable to follow up on his claim to the English throne because he was too busy battling for the rule of Denmark. Edward became the Anglo-Saxon ruler of England. Now with Mangus and Edward dead, Hardrada asserted that he, as Mangus's heir, was the rightful ruler of England. When he heard of Harold's coronation, Hardrada immediately prepared to invade England and crush the upstart.

Hardrada of Norway struck first. In mid September, Hardrada's invasion force landed on the Northern English coast, sacked a few coastal villages and headed towards the city of York. Hardrada was joined in his effort by Tostig, King Harold's nere-do-well brother. The Viking army overwhelmed an English force blocking the York road and captured the city. In London, news of the invasion sent King Harold hurriedly north at the head of his army picking up reinforcements along the way. The speed of Harold's forced march allowed him to surprise Hardrada's army on September 25, as it camped at Stamford Bridge outside York. A fierce battle followed. Hand to hand combat ebbed and flowed across the bridge. Finally the Norsemen's line broke and the real slaughter began. Hardrada fell and then the King's brother, Tostig. What remained of the Viking army fled to their ships. So devastating was the Viking defeat that only 24 of the invasion force's original 240 ships made the trip back home. Resting after his victory, Harold received word of William's landing near Hastings.

Construction of the Norman invasion fleet had been completed in July and all was ready for the Channel crossing. Unfortunately, William's ships could not penetrate an uncooperative north wind and for six weeks he languished on the Norman shore. Finally, on September 27, after parading the relics of St. Valery at the water's edge, the winds shifted to the south and the fleet set sail. The Normans made landfall on the English coast near Pevensey and marched to Hastings.

Harold rushed his army south and planted his battle standards atop a knoll some five miles from Hastings. During the early morning of the next day, October 14, Harold's army watched as a long column of Norman warriors marched to the base of the hill and formed a battle line. Separated by a few hundred yards, the lines of the two armies traded taunts and insults. At a signal, the Norman archers took their position at the front of the line. The English at the top of the hill responded by raising their shields above their heads forming a shield-wall to protect them from the rain of arrows. The battle was joined.

The English fought defensively while the Normans infantry and cavalry repeatedly charged their shield-wall. As the combat slogged on for the better part of the day, the battle's outcome was in question. Finally, as evening approached, the English line gave way and the Normans rushed their enemy with a vengeance. King Harold fell as did the majority of the Saxon aristocracy. William's victory was complete. On Christmas day 1066, William was crowned King of England in Westminster Abbey.

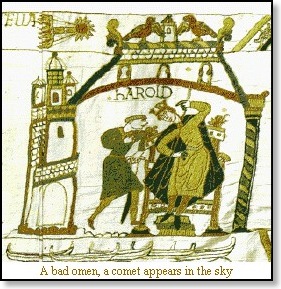

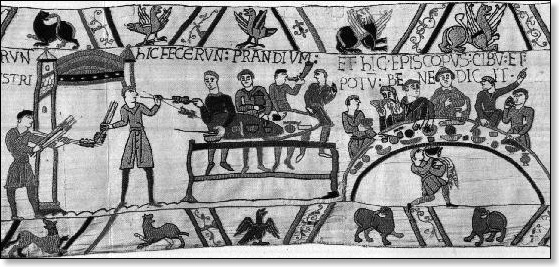

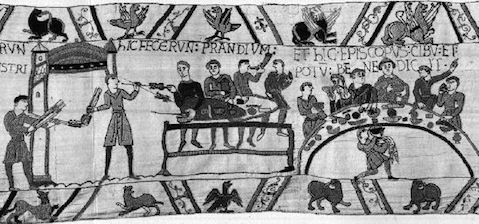

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry (actually an embroidery measuring over 230 feet long and 20 inches wide) describes the Norman invasion of England and the events that led up to it. It is believed that the Tapestry was commissioned by Bishop Odo, bishop of Bayeux and the half-brother of William the Conqueror. The Tapestry contains hundreds of images divided into scenes each describing a particular event. The scenes are joined into a linear sequence allowing the viewer to "read" the entire story starting with the first scene and progressing to the last. The Tapestry would probably have been displayed in a church for public view.

History is written by the victors and the Tapestry is above all a Norman document. In a time when the vast majority of the population was illiterate, the Tapestry's images were designed to tell the story of the conquest of England from the Norman perspective. It focuses on the story of William, making no mention of Hardrada of Norway nor of Harold's victory at Stamford Bridge. The following are some excerpts taken from this extraordinary document.

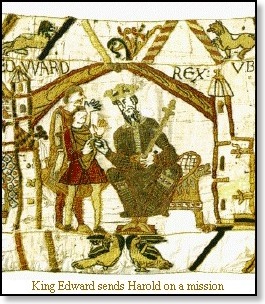

King Edward sends Harold on a Mission

The Tapestry's story begins in 1064. King Edward, who has no heirs, has decided that William of Normandy will succeed him. Having made his decision; Edward calls upon Harold to deliver the message.

This at any rate, is the Norman interpretation of events for King Edward's selection of William is critical to the legitimacy of William's later claim to the English crown. It is also important that Harold deliver the message, as the tapestry explains in later scenes.

In this scene King Edward leans forward entrusting Harold with his message. Harold immediately sets out on his fateful journey.

Harold Swears an Oath to William

Pursuing his mission, the Tapestry describes how Harold crosses the English Channel to Normandy, is held hostage by a Norman count and is finally rescued by William.

Harold ends up in William's castle at Bayeux on the Norman coast where he supposedly delivers the message from King Edward. At this point the Tapestry describes a critical event. Having received the message that Edward has anointed him as his successor; William calls upon Harold to swear an oath of allegiance to him and to his right to the throne. The Tapestry shows Harold, both hands placed upon religious relics enclosed in two shrines, swearing his oath as William looks on. The onlookers, including William, point to the event to add further emphasis. One observer (far right) places his hand over his heart to underscore the sacredness of Harold's action. Although William is seated, he appears larger in size than Harold. The disproportion emphasizes Harold's inferior status to William. The Latin inscription reads "Where Harold took an oath to Duke William."

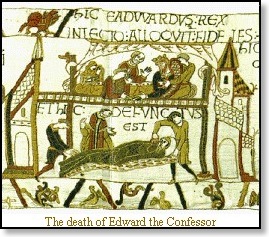

The Death and Burial of Edward the Confessor

The Tapestry describes Harold's return to England after swearing his oath to William and his report to King Edward. The story then advances forward two years to 1066 and the death of Edward.

The death and burial of King Edward is presented in three scenes whose chronological order is reversed. The first image (1) depicts Westminster Abbey. This is followed by Edward's funeral procession (2) and then his death (3).

The Death of Edward

In this scene (3) Edward is presented as both alive and dead. In the top portion of the panel Edward converses with those gathered at his bedside. The Latin inscription reads "Here King Edward addresses his faithful ones." At the foot of his bed sits Edward's wife who is also Harold's sister. At the side of the bed stands Stigand, the archbishop of Canterbury who performs a religious ceremony. The dying king addresses Harold who kneels in front of him. It is here that Edward supposedly anointed Harold as his successor giving legitimacy to Harold's claim to the crown.

In the lower panel Edward is prepared for burial. The bishop performs last rites while the embalmers go about their work. The Latin inscription reads "And here he died."

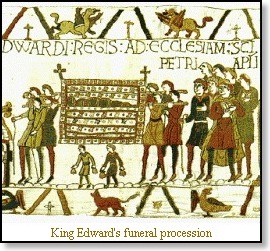

The Procession

Edwards' body, wrapped in linen, is carried to the church for burial (2). The Latin inscription reads "Here the body of King Edward is carried to the Church of St. Peter the Apostle." Edward's burial took place on January 6, 1066.

In its entry for the year 1066, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes Edward's death as follows: "In this year was consecrated the minster at Westminster, on Childer-mass-day. And King Edward died on the eve of Twelfth-day; and he was buried on Twelfth-day within the newly consecrated church at Westminster. And Harold the earl succeeded to the kingdom of England, even as the king had granted it to him, and men also had chosen him thereto; and he was crowned as king on Twelfth-day."

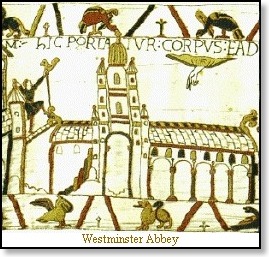

Westminster Abbey

Edward's funeral procession completes its journey at Westminster Abbey (1). King Edward began work on the abbey in 1050 and construction was completed shortly before his death. The pious Edward was awarded the distinction "the Confessor" for his effort. Unfortunately, the King fell ill on Christmas eve and was unable to attend the abbey's consecration.

The Tapestry conveys the newness of the abbey by the workman affixing the weather vane atop the roof to the left. God's blessing upon the consecrated structure is represented by the hand appearing from the clouds above.

A Bad Omen: the Appearance of Halley's Comet

Harold is crowned king on January 6. In the spring, near Easter, a comet appears in the sky. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes the event: "Easter was then on the sixteenth day before the calends of May. Then was over all England such a token seen as no man ever saw before. Some men said that it was the comet-star, which others denominate the long-hair'd star. It appeared first on the eve called 'Litania major', that is, on the eighth before the calends of May; and so shone all the week."

We now know that the comet-star in the sky was Halley's Comet making one of its 76-year cyclical appearances. In the Tapestry, an attendant rushes to tell Harold of the celestial happening as he sits upon his throne. The comet appears at the upper left. The portrayal acquires a sense of foreboding as empty long boats appear below the scene. These no doubt presage the invasion fleet William will employ to cross the Channel. The Tapestry implies that the appearance of the comet expresses God's wrath at Harold for breaking his oath to William and assuming the throne. Retribution will be found in the invasion fleet.

William Launches His Invasion

Upon hearing the news of Harold's coronation, William immediately orders the building of an invasion fleet. The Tapestry describes in detail the construction of the fleet and preparations for the invasion providing insight into eleventh century building techniques. With preparations complete, William waits on the Normandy shore for a favorable wind to take him to England.

The favorable wind arrives on September 27, and the fleet sets sail, its ships loaded with knights, archers, infantry, horses and the lumber necessary to build two or three forts. This scene shows William's ship as the fleet approaches Pevensy on the English shore. A cross adorns the top of the ship's mast. Below the cross, a lantern guides the way for the rest of the fleet. Shields line the ship's gunwales, reminiscent of the practice of the Norman's Viking ancestors. A dragon's head sits on the ship's prow and a bugler blows his horn at the ship's stern. A ship laden with horses sails along side William's craft. The fleet lands on September 28 and the invasion army makes its way to Hastings.

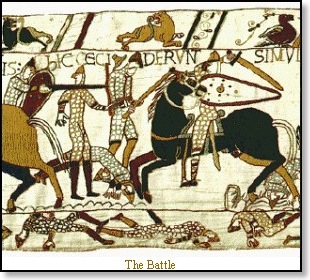

The Battle

This is one of many scenes depicting the ferocity of the battle. Wielding his battle-axe, a Saxon deals a death-blow to the horse of a Norman. This was the first time the Normans had encountered an enemy armed with the battle-axe. For the Saxons, this was the first time they had battled an enemy mounted on horseback. This scene probably describes the later stages of the battle when the Norman knights had broken through the Saxon shield wall. At the bottom of the scene lay the dead bodies of both Normans and Saxons.

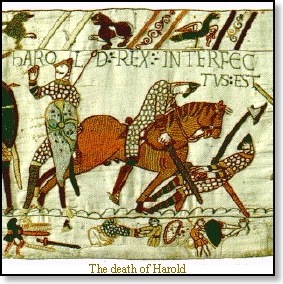

The Death of Harold

King Harold tries to pull an arrow from his right eye. Several arrows are lodged in his shield showing he was in the thick of the battle. To the right, a Norman knight cuts down the wounded king assuring his death. At the bottom of the scene the victorious Normans claim the spoils of war as they strip the chain mail from bodies while collecting shields and swords from the dead. Scholars debate the meaning of this scene, some saying that the man slain by the knight is not Harold, others contesting that the man with the arrow wound is not Harold, others claiming that both represent Harold. The Latin inscription reads "Here King Harold was killed." The Tapestry ends its story after the death of Harold.

William ruled England until his death in 1087. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recalls the Norman King in its entry for that year: "But amongst other things is not to be forgotten that good peace that he made in this land; so that a man of any account might go over his kingdom unhurt with his bosom full of gold. No man durst slay another, had he never so much evil done to the other; and if any churl lay with a woman against her will, he soon lost the limb that he played with. He truly reigned over England; and by his capacity so thoroughly surveyed it, that there was not a hide of land in England that he wist not who had it, or what it was worth, and afterwards set it down in his book."

References:

Bernstein, David, The Mystery of the Bayeux Tapestry (1987); Howarth, David, 1066 the Year of the Conquest (1978); Ingram, James (translator), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (1823); Wood, Michael, In Search of the Dark Ages (1987).

Resources on the Web:

Battle of Hastings, 1066

Bayeux Tapestry

![]()

G.B. - William the Conqueror

Welcome to the royal Genealogy information held at University of Hull .

William I the Conqueror, King of England

Born: 1028, Falaise,Normandy,France

Acceded: 25 DEC 1066, Westminster Abbey, London, England

Died: 9 SEP 1087, Hermentrube, Near Rouen, France

Interred: St Stephen Abbey,Caen,Normandy

Notes:

Reigned 1066-1087. Duke of Normandy 1035-1087. Invaded England defeated and

killed his rival Harold at the Battle of Hastings and became King. The Norman

conquest of England was completed by 1072 aided by the establishment of

feaudalism under which his followers were granted land in return for pledges

of service and loyalty. As King William was noted for his efficient if harsh

rule. His administration relied upon Norman and other foreign personnell

especially Lanfranc Archbishop of Canterbury. In 1085 started Domesday Book.

Father: Normandy, Robert II the Devil of, Duke of Normandy 6th, b. CIR 1008

Mother: , Herleva (Arlette), Officer of the Household, b. CIR 1012

Married 1053, Cathedral of Notre Dame d'Eu, Normandy to , Matilda of Flanders

Child 1: , Robert II Curthose, Duke of Normandy, b. 1054

Child 2: , Richard, Duke of Bernay, b. ABT 1055

Child 3: , Cecilia of Holy Trinity, Abbess of Caen, b. 1056

Child 4: , Adeliza, Nun, b. 1055

Child 5: , William II Rufus, King of England, b. 1056/60

Child 6: , Constance, b. ABT 1066

Child 7: , Adela, Countess of Blois, b. ABT 1067

Child 8: , Agatha, b. ABT 1064

Child 9: , Matilda

Child 10: , Henry I Beauclerc, King of England, b. ABT SEP 1068

With his victory at the Battle of Hastings, William became known as William "the Conquerer." Prior to this, he was known as William "the Bastard" because he was the result of his father's affair with a tanner's daughter.

Before the battle, William vowed that if granted victory, he would build an Abbey on the battleground with its altar at the spot where Harold's standards stood. William was true to his word and Battle Abbey stands today at the site of the battle.

During the later years of his reign, Edward withdrew from many of his kingly responsibilities. Harold filled this void and became virtual ruler of England.

William was made Duke of Normandy at age seven. His ascension ignited a civil war lasting 12 years.

![]()

G.B. - Legend

Battle, East Sussex![]()

It is said that at the Battle of Hastings, now preserved in the place name Battle, the flag raised by King Harold was painted with a golden dragon. This is almost certainly true, for this dragon appears twice on the famous Bayeux Tapestry, which was embroidered to commemorate this historic fight that so influenced the future history of Britain. This dragon is sometimes called 'The Golden Dragon of Wessex', because it was said to have been carried by Cuthred of Wessex at the battle of Burford in AD 752, yet it appears to have been originally used by Saxon tribes on the Continent. It seems that when the West Saxons invaded Britain in AD 495, they carried a golden dragon as their standard. The dragon appeared on the standards of at least four of William's successors, and in his account of the crusade undertaken by Richard I, the chronicler Ricard of Devizes mentions 'The terrible standard of the dragon...borne in front unfurled'. According to the records, the dragon on the standard of Henry III was made of red silk, 'sparkling all over with gold', its tongue like burning fires, and its eyes made of 'sapphires or some other suitable stones'. It was a dragon of this descent which was unfurled to witness the English victory at Agincourt, though it is not the same dragon which is nowadays mis-called a 'griffin' on the shield of the city of London. There are many myths and legends attached to the Battle of Hastings, almost all of them elaborations. The most famous tells how Richard le Fort, seeing William in danger, threw his own shield in front of him, thereby saving him from being killed. For this reason, it is claimed, Fort was permitted to add to his name 'escue' ('shield'), hence the modern name for the family, as Fortesque. The story is almost certainly apochryphal, though the family's motto is a pun on their name, reading in Latin 'Forte scutum salvus ducum' (A strong shield is the leader's safety).

![]()

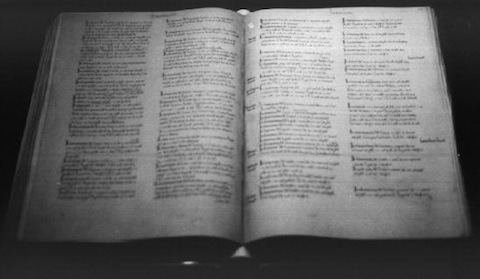

G.B. - Domesday book

DOMESDAY (Continued)

PLATE 12

The lower fort/first meal

Next follows the serving of the first meal after the erection of the wooden fort that they are reported to have bought with them. This plate shows the first fort that they built as two towers connected by a roof that could be constructed from parts of the dismantled ships. This would support Wace's claim that the ships were dismantled. It would clearly be a logical thing to do as the timbers from so many ships would form a readily accessible timber source with which to build a fort. These defences can be seen with what may be the oar ports intact, exactly as portrayed earlier (Plate 9 and Plate 10) as white holes in black timber.

Placing the foot of the tower upon the base of the Tapestry leads me to believe this site to be at the bottom of the hill described in the Chronicle of Battle Abbey and Wace's Roman de Rue. The coloured curved strips, seen behind the fort, could also indicate a hill. These strips being a diagrammatic way of showing the way that farmers sowed crops across fields to facilitate ploughing by oxen. This seems a logical explanation but does not satisfactorily explain the existence of a projection at the top of the curve. Whilst not apparent on most reproductions in print it is very obvious when viewed in person at the Bayeux gallery.

THE SECRETS OF

THE NORMAN INVASION©

BY NICK AUSTIN

PART 1 THE LANDING SITE

It is the intention of this document together with the one currently under research to bring to the attention of the reader new evidence concerning the events of the Norman Invasion. The evidence in this text relates purely to establishing the correct site of the Invasion and Norman camp from the examination of authentic manuscript documents of the time, in conjunction with geographical and archaeological evidence, that has never before been available. I shall show that where descriptions in one manuscript might be considered contradictory to statements in another, the actual events of the time can be explained in a rational and logical way once the correct site is known. It is the intention to show the reader in a detailed manner evidence that rewrites our previous understanding of history concerning what is considered by many to be the most important singular event in English history - the Norman Invasion.

This document relates solely to those matters relevant to the landing of the Norman Invasion fleet and the circumstances concerning the period up until the Norman army left to fight the Battle of Hastings. Having established the authentic landing and camp site, where the Norman army was based, many more questions are raised concerning the events of the day of the Battle of Hastings. These too have remained a mystery to those who have studied the fine details and I propose to be the first to answer all of the outstanding questions leaving no matter unresolved. However, due to the recent decision by the Department of Transport to build a major trunk road through the centre of the landing site, I have no alternative but to publish my initial findings now. The alternative could be the loss of a site of national historical and archaeological importance, which would be wholly unacceptable. In consequence and in the interests of all concerned I propose to deal with these further matters in a second volume, titled THE BATTLE OF HASTINGS, at a later date.

MANUSCRIPT EVIDENCE

It is necessary to look initially at what the written historical record tells us about the events of the time. I have therefore only taken into account those manuscripts that are believed to originate within 150 years of the date of the Battle and that can throw light on the events of the landing. It is not my intention to prove or disprove the authenticity of the writings contained in the texts examined. It is my belief that all of them reported the events of the time, in an honest manner, to the best of their ability. The discrepancies that occur in consequence of seeking to apply the substance of these texts to the wrong landing site are studied in detail and instead of supporting the argument that any of the documents are unreliable, effectively endorses their accuracy when applied to the correct site. Thus all the manuscripts examined have a thorough consistency valid to only one landing site.

![]()

G.B. - The norman Invasion

THE SECRETS OF

THE NORMAN INVASION©

BY NICK AUSTIN

PART 1 THE LANDING SITE

It is the intention of this document together with the one currently under research to bring to the attention of the reader new evidence concerning the events of the Norman Invasion. The evidence in this text relates purely to establishing the correct site of the Invasion and Norman camp from the examination of authentic manuscript documents of the time, in conjunction with geographical and archaeological evidence, that has never before been available. I shall show that where descriptions in one manuscript might be considered contradictory to statements in another, the actual events of the time can be explained in a rational and logical way once the correct site is known. It is the intention to show the reader in a detailed manner evidence that rewrites our previous understanding of history concerning what is considered by many to be the most important singular event in English history - the Norman Invasion.

This document relates solely to those matters relevant to the landing of the Norman Invasion fleet and the circumstances concerning the period up until the Norman army left to fight the Battle of Hastings. Having established the authentic landing and camp site, where the Norman army was based, many more questions are raised concerning the events of the day of the Battle of Hastings. These too have remained a mystery to those who have studied the fine details and I propose to be the first to answer all of the outstanding questions leaving no matter unresolved. However, due to the recent decision by the Department of Transport to build a major trunk road through the centre of the landing site, I have no alternative but to publish my initial findings now. The alternative could be the loss of a site of national historical and archaeological importance, which would be wholly unacceptable. In consequence and in the interests of all concerned I propose to deal with these further matters in a second volume, titled THE BATTLE OF HASTINGS, at a later date.

MANUSCRIPT EVIDENCE

It is necessary to look initially at what the written historical record tells us about the events of the time. I have therefore only taken into account those manuscripts that are believed to originate within 150 years of the date of the Battle and that can throw light on the events of the landing. It is not my intention to prove or disprove the authenticity of the writings contained in the texts examined. It is my belief that all of them reported the events of the time, in an honest manner, to the best of their ability. The discrepancies that occur in consequence of seeking to apply the substance of these texts to the wrong landing site are studied in detail and instead of supporting the argument that any of the documents are unreliable, effectively endorses their accuracy when applied to the correct site. Thus all the manuscripts examined have a thorough consistency valid to only one landing site.

DOMESDAY (Continued)

PLATE 12

Part Twenty-one

PLATE 12

The lower fort/first meal

Next follows the serving of the first meal after the erection of the wooden fort that they are reported to have bought with them. This plate shows the first fort that they built as two towers connected by a roof that could be constructed from parts of the dismantled ships. This would support Wace's claim that the ships were dismantled. It would clearly be a logical thing to do as the timbers from so many ships would form a readily accessible timber source with which to build a fort. These defences can be seen with what may be the oar ports intact, exactly as portrayed earlier (Plate 9 and Plate 10) as white holes in black timber.

Placing the foot of the tower upon the base of the Tapestry leads me to believe this site to be at the bottom of the hill described in the Chronicle of Battle Abbey and Wace's Roman de Rue. The coloured curved strips, seen behind the fort, could also indicate a hill. These strips being a diagrammatic way of showing the way that farmers sowed crops across fields to facilitate ploughing by oxen. This seems a logical explanation but does not satisfactorily explain the existence of a projection at the top of the curve. Whilst not apparent on most reproductions in print it is very obvious when viewed in person at the Bayeux gallery.

This “nipple”, as I shall call it, makes further inference to the fact that the strips may not have been meant to be interpreted as a hill but some form of roof. The fact that it matches the planking on the invasion boats may be just co-incidence. All that is certain is that the designers wished to draw this particular item to our attention.

There then follows a meal where two sets of people are dining.

The first, on the left, are using their shields as a table raised above the normal ground level, illustrating the resourceful use of materials bought with them. The second dining scene appears to be at a similar elevation but this time in a circular room. It has been suggested that the presentation is of a circular table. I do not believe this is the case, as the artist is showing an important scene which took place on the day of the landing, confirmed by Wace's manuscript. It illustrates a number of stages of the same meal in one picture, demonstrating the skill of the originators, to save time in production and achieve the maximum impact. The fact that the table is tapered indicates that it has been specifically designed to show some form of perspective, which in turn means in my view that the room was round, rather than the table.

The man in front is a servant with hand basin and towel for hand washing. Bishop Odo is the dominant figure blessing the food. The duke sits at the right of the Bishop with one hand in a dish taking the meal. The man the other side of Odo is signalling that the meal is over and it is time to leave. There is only one implement on the table and that is a knife, the only eating implement of the age.

An important aspect of this section of the Tapestry is that the landing sequence, when seen in total, is a continuous event up to this point. Bishop Odo is shown with a fish on the table, together with fish in front of one or possibly two of the other guests. This provides almost conclusive evidence that these events took place on a Friday, when clerics abstained from meat. The 29th September was the Friday in question, the day of the landing, therefore this meal must have been taken in the Norman camp on the first day or night of the Invasion. The Saxon Chronicles, which we shall look at in the next chapter, provide very little evidence about the Invasion, other than confirming that the Normans left St Valery on the night of Thursday 28th September. This is also confirmed by the Carmen where it states

"The feast of St Michaell was about to be celebrated throughout the world when God granted everything according to your desire".

The Bayeux Tapestry provides us with a unique detail that could easily be over looked. There was not enough time or tide for the invaders to have landed in the morning at Pevensey and then sailed or marched on to Hastings to arrive there on the same day as the landing (which was the Friday). The reason for showing the bishop eating fish, whilst the other men ate provisions, was to confirm the bishop's position as spiritual leader. In many respects the picture in the tapestry takes on the spiritual aspirations of the last supper, with Bishop Odo occupying the leading roll. The meal was a significant event since Wace reports the same supper. It was known to everyone, at the time, that this took place on the day of the landing and this was a Friday. Hence the requirement for a fish at the table of the bishop. The consequence of this analysis is that contrary to previous historical thinking the Bayeux Tapestry provides further unexpected and incontrovertible proof by virtue of the logistics of the day that Hastings was the landing site.

![]()

France - Dives - Compagnons de Guillume le Conquérant

LIST OF THOSE ACCOMPANYING WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR

ON HIS INVASION OF ENGLAND

1066

This list is taken from the plaque in the church at Dives-sur-Mer, Normandy, France, where William the Conqueror and his knights said mass before setting sail to invade England in 1066.

It lists all the knights who took part in the invasion. Care needs to be taken in using this list:

1) In the first place, it is ordered by Christian name, not by surname.

2) Secondly the concept of surnames as we know them was not very well-developed. In most cases, they either took the names of the villages whence they came (this would generally be the case for those those starting with a "de"), or else the surname was a sort of nickname, depicting certain characteristics e.g. Alain le Roux (Alain of the red hair), Raoul Vis-de-Loup (Raoul wolf-face) etc.

And then of course we have poor Robert Le Bastard....

In other cases, it could be the father's name, in the format "fils de...." (= son of..... ). This in later years became"Fitz....", as in such names as "Fitzjohn" etc.

3) The spellings were often different then. For example, the family name Bunker comes from French Bon-Coeur ("Good-Heart). This would have been written "Cor-bon" in Norman French. Also, the bishop of Bayeux, who is normally known by the name of "Odo", is listed under the French spelling of "Eude".

4) Please remember that these names would have been copied, recopied and miscopied several times, so errors could well creep in. Handwritten "u"s and "n"s would tend to get confused, as might "e"s and "a"s.

Achard d'Ivri

Alevi

Altard de Vaux

Alain le Roux

Ansure de Dreux

Anquetil de Cherbourg

Anquetil de Grai

Anquetil de Ros

Anscoul de Picvini

Ansfroi de Cormeilles

Ansfroi de Vaubadon

Ansger de Montaigu

Ansger de Senarpont

Ansgot

Ansgot de Ros

Arnould de Perci

Arnould d'Andre (Arnould d'Andri)

Arnould de Nesdin

Aubert Greslet

Aubri de Couci

Aubri de Ver

Auvrai le Breton

Auvrai d'Espagne

Auvrai Merteberge

Auvrai de Tanie

Azor

Bavent

Beaudouin de Colombieres (Beaudouin de Colombihres)

Beaudoin le Flamand

Beaudoin de Meules

Berenger Giffard

Berenger de Toeni

Bernard d'Alencon (Bernard d'Alengon)

Bernard de Neufmarche

Bernard Pancevolt

Bernard de Saint-Ouen

Bertran de Verdun

Beugelin de Dive

Bigot de Loges

Carbonnel

Daniel

Danneville

David d'Argentan

D'Argouges

D'Auvay

D'Auvrecher d'Angerville

de Bailleul

de Briqueville (*)

de Canouville

De Clinchamps

De Courcy

de Cugey

de Fribois

d'Hericy

d'Houdetot

de Mathan

de Montfiquet

d'Orglande

du Merle

(* This name is duplicated - not clear whether there were two)

de Saint-Germain

de Sainte-d'Aignaux

de Tilly

de Touchet

de Tournebut

de Venois

Drew de la Berviere (Drew de la Bervihre)

Drew de Montaigu

Durand Malet

Ecouland

Engenouf de l'Aigle

Engerrand de Rainbeaucourt

Erneis de Buron

Etienne de Fontemai

Eude Comte de Champagne

Eude Eveque de Bayeux (Eude Evjque de Bayeux)

Eude Cul de Louf

Eude le Flamand

Eude de Fourneaux

Eude le Senechal (Eude le Sinichal)

Eustache Comte de Boulogne

Foucher de Paris

Fouque de Libourg

Gautier de l'Appeville

Gautier le Bouguignon

Gautier de Caen

Gautier de Claville

Gautier de Douai

Gautier Giffard

Gautier de Grancourt

Gautier Hachet

Gautier Hewse

Gautier d'Incourt

Gautier de Laci

Gautier de Mucedent

Gautier d'Ornontville

Gautier de Riebou

Gautier de Saint-Valeri (Gautier de Saint-Valiri)

Gautier Tirel

Gautier de Vernon

Geoffroi Albelin

Geoffroi Bainard

Geoffroi du Bec

Geoffroi de Cambrai

Geoffroi de la Guierche

Geoffroi le Marechal

Geoffroi de Mandeville

Geoffroi Martel

Geoffroi Maurouard

Geoffroi de Montbrai

Geoffroi Comte du Perche

Geoffroi de Pierrepont

Geoffroi de Ros

Geoffroi de Runeville

Geoffroi Talbot

Geoffroi de Tournai

Geoffroi de Trelli

Gerboud le Flamand

Gilbert le Blond

Gilbert de Blosbeville

Gilbert de Bretteville

Gilbert de Budi

Gilbert de Colleville

Gilbert de Gand

Gilbert de Gibard

Gilbert Malet

Gilbert Maminot

Gilbert Tibon

Gilbert de Werables

Gilbert de Wissant

Gonfroi de Cioches

Gonfroi Mauduit

Goscelin de Corneilles

Goscelin de Douai

Goscelin de la Riviere (Goscelin de la Rivihre)

Goubert d'Aufai

Goubert de Beauvais

Guernon de Peis

Gui de Craon

Gui de Raimbeaucourt

Gui de Rainecourt

Guillaume Alis

Guillaume d'Angleville

Guillaume l'Archer

Guillaume d'Argues

Guillaume d'Audrieu

Guillaume de l'Aune

Guillaume Basset

Guillaume Belet

Guillaume de Beaufou

Guillaume Bertran

Guillaume de Biville

Guillaume le Blond

Guillaume Bonvalet

Guillaume de Bosc

Guillaume du Bosc-Roard

Guillaume de Bourneville

Guillaume de Brai

Guillaume de Briouse

Guillaume de Bursigni

Guillaume de Canaigres

Guillaume de Cailli

Guillaume de Cairon

Guillaume Cardon

Guillaume de Carnet

Guillaume de Castillon

Guillaume de Ceauce

Guillaume la Cleve

Guillaume de Colleville

Guillaume de Paumera

Guillaume le Despensier

Guillaume de Durville

Guillaume d'Ecouis

Guillaume Espec

Guillaume d'Eu

Guillaume Comte d'Evreux

Guillaume de Falaise

Guillaume de Fecamp (Guillaume de Ficamp)

Guillaume Folet

Guillaume de la Foret

Guillaume de Fougeres (Guillaume de Foughres)

Guillaume Froissart

Guillaume Goulaffre

Guillaume de Letre

Guillaume de Loucelles

Guillaume Louvet

Guillaume Malet

Guillaume de Malleville

Guillaume de la Mare

Guillaume Maubenc

Guillaume Mauduit

Guillaume de Moion

Guillaume de Monceaux

Guillaume de Noyers

Guillaume fils d'Olgeanc

Guillaume Pantoul

Guillaume de Parthenai

Guillaume Peche

Guillaume de Perci

Guillaume Pevrel

Guillaume de Piquiri

Guillaume Poignant

Guillaume de Poillei

Guillaume le Poitevin

Guillaume de Pont de l'Arche

Guillaume Quesnel

Guillaume de Reviers

Guillaume de Sept-Meules

Guillaume Taillebois

Guillaume de Tocni

Guillaume de Vatteville

Guillaume de Vauville

Guillaume de Ver

Guillaume de Vesli

Guillaume de Warenne

Guimond de Blangi

Guimond de Tessel

Guineboud de Balon

Guinemar le Flamand

Hamelin de balon

Hamon le Senechal (Hamon le Sinichal)

Hardouin d'Escalles

Hascouf Musard

Henri de Beaumont

Henri de Ferrieres (Henri de Ferrihres)

Herman de Dreux

Herve le Berruier (Hervi le Birruier)

Herve d'Espagne (Hervi d'Espagne)

Herve d'Helion (Hervi d'Hilion)

Honfroi d'Ansleville

Honfroi de Biville

Honfroi de Bohon

Honfroi de Carteret

Honfroi de Culai

Honfroi de l'ile

Honfroi du Tilleul

Honfroi Vis-de-Louf

Huard de Vernon

Hubert de Mont-Canisi

Hubert de Pont

Hugue l'Ane

Hugue d'Avranches

Hugue de Beauchamp

Hugue de Bernieres (Hugue de Bernihres)

Hugue du Bois-Hebert (Hugue du Bois-Hibert)

Hugue de Bolbec

Hugue Bourdet

Hugue de Brebeuf

Hugue de Corbon

Hugue de Dol

Hugue le Flamand

Hugue de Gournai

Hugue de Grentemesnil

Hugue de Guideville

Hugue de Hodenc

Hugue de Hotot

Hugue d'Ivri

Hugue de Laci

Hugue de Maci

Hugue Maminot

Hugue de Manneville

Hugue de la Mare

Hugue Mautravers

Hugue de Mobec

Hugue de Montfort

Hugue de Montgommeri

Hugue Musart

Hugue de Port

Hugue de Rennes

Hugue de Saint-Quentin

Hugue Silvestre

Hugue de Vesli

Hugue de Viville

Ilbert de Laci

Ilbert de Toeni

Ive Taillebois

Ive de Vesci

Jasce le Flamand

Jumel de Toeni

Lanfranc

le Vicomte

Mathieu de Mortagne

Mauger de Carteret

Maurin de Caen

Mile Crespin

Murdac

Niel d'Aubigni (Niel d'Aubigni)

Niel de Berville (Niel de Berville)

Niel Fossard (Niel Fossard)

Niel de Gournai (Niel de Gournai)

Niel de Munneville (Niel de Munneville)

Normand d'Adreci

Osberne d'Arques

Osberne du Breuil

Osberne d'Eu

Osberne Giffard

Osberne Pastforeire

Osberne du Quesnai

Osberne du Saussai

Osberne de Warci

Osmond

Osmont de Vaubadon

Oure d'Addetot

Oure de Bercheres

Picot

Pierre de Valognes

Rahier d'Avre

Raoul d'Aunon

Raoul Baignard

Raoul de Bans

Raoul de Bapaumes

Raoul Basset

Raoul de Beaufou

Raoul de Bernai

Raoul Blouet

Raoul Botin

Raoul de la Bruiere (Raoul de la Bruihre)

Raoul de Chartres

Raoul de Colombieres (Raoul de Colombihres)

Raoul de Conteville

Raoul de Courseume

Raoul de l'Estourmi

Raoul de Fougeres (Raoul de Foughres)

Raoul de Framan

Raoul de Gael

Raoul de Hauville

Raoul L'ile

Raoul de Lanquetot

Raoul de Linesi

Raoul de Marci

Raoul de Mortemer

Raoul de Moron

Raoul d'Ouilli

Raoul Painel

Raoul Pinel

Raoul Pipin

Raoul de la Pommeraie

Raoul du Quesnai

Raoul de Saint-Sanson

Raoul du Saussai

Raoul de Sauvigni

Raoul Taillebois

Raoul du Theil

Raoul de Toeni

Raoul de Tourlaville

Raoul de Tourneville

Raoul Tranchant

Raoul fils d'Unepac

Raoul Vis-de-Loup

Ravenot

Renaud de Bailleul

Renaud Croc

Renaud de Pierrepont

Renaud de Saint-Helene (Renaud de Saint-Hilhne)

Renaud de Torteval

Renier de Brimou

Renouf de Colombelles

Renouf Flambard

Renouf Pevrel

Renouf de Saint-Waleri

Renouf Vaubadon

Richard Basset

Richard de Beaumais

Richard de Bienfaite

Richard de Bondeville

Richard de Courci

Richard d'Engagne

Richard L'Estourmi

Richard Fresle

Richard de Meri

Richard de Neuville

Richard Poignant

Richard de Reviers

Richard de Sacquerville

Richard de Saint-Clair

Richard de Sourdeval

Richard Talbot

Richard de Vatteville

Richard de Vernon

Richer d'Andeli

Robert d'Armentieres (Robert d'Armentihres)

Robert d'Auberville

Robert d'Aumale

Robert de Barbes

Robert Le Bastard

Robert de Beaumont

Robert Le Blond

Robert Blouet

Robert Bourdet

Robert de Brix

Robert de Buci

Robert de Chandos

Robert Corbet

Robert de Courcon (Robert de Courgon)

Robert Cruel

Robert le Despensier

Robert Comte d'Eu

Robert Fromentin

Robert fils de Gerould

Robert de Glanville

Robert Guernon

Robert de Harcourt

Robert de Lorz

Robert Malet

Robert Comte de Meulan

Robert de Montbrai

Robert de Montfort

Robert Comte de Mortain

Robert des Moutiers

Robert Murdac

Robert d'Ouilli

Robert de Pierrepont

Robert de Pontchardon

Robert de Rhuddlan

Robert de Romenel

Robert de Saint-Leger

Robert de Thaon

Robert de Toeni

Robert de Vatteville

Robert des Vaux

Robert de Veci

Robert de Vesli

Robert de Villon

Roger d'Aubernon

Roger Arundel

Roger d'Auberville

Roger de Beaumont

Roger Bigot

Roger Boissel

Roger de Bosc-Normand

Roger de Bosc-Roard

Roger de Breteuil

Roger de Bulli

Roger de Carteret

Roger de Chandos

Roger Corbet

Roger de Courcelles

Roger d'Evreux

Roger d'Ivri

Roger de Laci

Roger de Lisieux

Roger de Meules

Roger de Montgommeri

Roger de Moyaux

Roger de Mussegros

Roger de Ouistreham

Roger d'Orbec

Roger Picot

Roger de Pistres

Roger le Poitevin

Roger de Rames

Roger de Saint-Germain

Roger de Somneri

Ruaud l'Adoube

Seri d'Auberville

Serlon de Burci

Serlon de Ros

Sigan de Cioches

Simon de Senlis

Thierri Pointel

Toustain

Turold

Turold de Grenteville

Turold de Papelion

Turstin de Gueron

Turstin Mantel

Turstin de Saint-Helene (Turstin de Saint-Hilhne)

Turstin fils de Rou

Turstin Tinel

Vauquelin de Rosai

Vital

Wadard

Companions of Duke William at Hastings

A combination of all the known Battell Abbey Rolls, including Wace, Dukes, Counts, Barons, Seigneurs who attended William at Hastings.

These were the commanders. They were the elite who had provided ships, horses, men and supplies for the venture. They were granted the Lordships.

The list does not include the estimated 12,000, Standard bearers, Men at Arms, Yeomen, Freemen and other ranks, although some of these were granted smaller parcels of England, some even as small as 1/8th of a knight's fee.

• A

Ours d'Abbetot

Roger d'Abernon

Ruaud d'Adoube (Musard)

Engenoulf de l'Aigle

Richard de l'Aigle (de Aquila)

Herbert d'Aigneaux

Guatier d'Aincourt

Guillaume Alis

Guillaume d'Alre

Archard d'Ambrieres

Robert d'Amfreville

le Sire de Anisy

Guillaume d'Anneville

Guatier d'Appeville

Guillaume L'Archer

Norman D'Arcy

Arnoul d'Ardre

David d'Argentan

Le Sire d'Argouges

Robert d'Armentieres

Guillaume d'Arques

Osbern d'Arques

Bagod d'Arras

Roger Arundel

Geoffroi Ascelin

Hugh L'Asne

Gilbert d'Asnieres

Raoul d'Asnieres

Guillaume d'Aubigny

Le Sire d'Aubigny (Roger)

Guillaume d'Audrieu

Gilbert d'Aufay

Fouque Aunou

Le Sire d'Auvillers

Richard Vicomte d'Avranches

B

Guaillaume Bacon Sire de Molay

Le Sire de Bailleul

Guineboud de Balon

Hamelin de Balon

Robert Banastre

Osmond Basset

Raoul Basset

Robert Le Bastard

Endes, Eveque de Bayeux

Hugue de Beauchamp

Guillaume de Beaufou

Robert de Beaufou

Robert de Beaumont

Gautier du Bec

Geoffroi du Bec

Hugue de Bernieres

Guillaume Bertram

Robert Bertram, le Tort

Le Sire de Beville

Avenel des Biards

Richard de Bienfaite et d'Orbec

Guillaume Bigot

Robert Bigot, Seigneur de Maltot

Gilbert Le Blond

Robert Le Blond

Robert Blouet

Blundel

Honfroi de Boho

Hugue de Bolbec

Le Sire de Bolleville

Le Sire de Bonnesboq

Guillaume de Bosc

Le Sire de Bosc-Roard(Simon)

Raoul Botin

Eustach, Comte de Boulogne

Hugue Bourdet

Robert Bourdet

Herve de Bourges

Guillaume de Bourneville

Hugue de Bouteillier

Le Sir de Brabancon

Guillaume de Brai

Raoul de Branch

Le Seigneur de Brecey

Robert de Breherval

Brian de Bratagne, Comte de Vennes

Roger de Breteuil

Anvrai Le Breton

Gilbert de Bretteville

Dreu de La Beuvriere

Guillaume de Briouse

Adam de Brix

Guillaume de Brix

Le Sire de Brucourt

Robert de Buci

Serion de Burci

Michel de Bures

C

Guatier de Caen

Maurin de Caen

Guillaume de Cahaignes

Guillaume de Cailly

Le Sire de Canouville(Gautier)

Hugue Carbonnel

Honfroi de Carteret

Eudes, Comte de Champagne

Robert de Chandos

Guillaume Le Chievre

Le Sire de Cintheaux

Gonfroi de Cioches

Hamon de Clervaux

Le Sire de Clinchamps

Robert de Cognieres

Gilbert de Colleville

Guillaume de Colombieres

Geoffroi de Combray

Robert de Comines

Amfroi de Conde

Alric Le Coq

Guillaume Corbon

Hugue Corbon

Aubri de Couci

Roger de Courcelles

Richard de Courci

Robert de Courson

Geoffroi, Eveque de Coutances

Le Sire de Couvert

Gui de Craon

Gilbert Crispin

Guillaume Crispin

Mile Crispin

Hamon Le Seneschal, Sir de Crevecoeur

Robert de Crevecoeur

Ansger de Criquetot

Le Sire de Cussy

D

Roger Daniel

Rober le Despensoer

Henri de Domfront

Gautier de Douai

Le Sire de Driencourt

E

Richard de'Engagne

Le Sire d'Epinay

Etienne Erard

Le Sire d'Escalles

Auvrai d'Espagne

Herve d'Espagne

Raoul L'Estourni

Richard L'Estourni

Robert d'Estouteville

Robert Count d'Eu

Gautier Le Ewrus(Roumare or Rosmar)

Guillaume, Count d'Evreux

Roger d'Evreux

F

Alain Fergant, Count de Bratagne

Guillaume de Ferrieres

Mathieu de la Ferte Mace

Guatier Fitz Autier

Fitz Bertran de Peleit

Adam Fitz Durand

Robert Fitz Erneis

Alain Fitz Flaald

Guillaume Fitz Osberne

Robert Fitz Picot

Robert Fitz Richard

Toustain Fitz Rou

Eudes Fitz Sperwick

Guatier Le Flamand

Raoul de Fourneaux

Le Sire de Fribois

G

Le Sire de Gace

Raoul de Gael

Gilbert de Gand

Berenger Giffard

Gautier Giffard, Count de Longueville

Osberne Giffard

Le Sire de Glanville

Le Sire de Glos

Ascelin de Gournay

Hugh de Gournay

Guillaume de Gouvix

Anchetil de Gouvix

Hugue de Grentiemesnil

Robert de Grenville

Robert Guernon, Sire de Montifiquet

Hugue de Guidville

Geoffroi de la Guierche

H

Gautier Hachet

Eudes le Seneschal, Sir de la Hale

Errand de Harcourt

Herve de Helion

Hugue d'Hericy

Tithel de Heron

Robert Heuse

Hugue d'Houdetot

I

Jean d'Ivri

Roger d'Ivry

Le Sire de Jort

L

Guillaume de Lacelles,

Gautier de Lacy

Ibert de Lacy

Baudri de Limesi

Auvrai de Lincoln

Ingleram de Lions

Le Sire de Lithaire