Hugh Fortescue (Sport)

Brooklands Stories![]()

Brooklands, Amphitheatre, Racetrack and Aviation Centre.

Brooklands was the brainchild of a wealthy landowner, Hugh Fortesque Locke-King who decided during a European tour in 1906 that Britain had to have its own motor testing track if it's fledgling car industry was to develop and prosper in competition with the Europeans.

So just who was Hugh Locke-King and what was on the site originally?

At the beginning of this century the area south of Weybridge High Street in Surrey, England was know as Weybridge Heath, a sizeable tract of land bounded on one side by the River Wey and on the other by St. George's Hill. In the Iron Age there had been a village on the heath and the Romans had walked the land in the early days of Christianity.

Brooklands took its name from the 12th century lord of the manor, Robert del Brok. In the sixteenth century Henry VIII used it as a hunting ground, his local residence being Oatlands Palace. The 700 acres that made up Brooklands Farm and Byfleet Park Farm were owned, during the 19th century, by the Duke of York who sold them for £28,000 in 1830 to Peter King the 7th Baron of Ockham. Hugh Locke-King was Peter King's son; the man who was to build Brooklands.

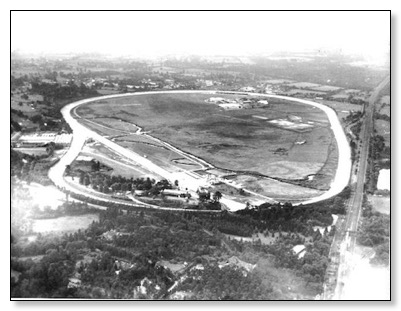

The site, approximately 300 acres of swampy and wooded land was crossed by the River Wey, bounded to the west by a railway, even boasted it's own sewage works. In retrospect it may not sound like an ideal proposition for building a 100 foot wide egg shaped, banked concrete race track measuring about 2.75 miles around, but this was to become Brooklands, the world's first real race track, enclosing its own aerodrome (click here for aerial view). Within months Brooklands was to become world famous, to endure as a centre of technical innovation in motor racing for thirty one years and in aviation for considerably longer than anyone could have possibly imagined in 1907, now almost ninety years ago.

In Europe, motor racing on public roads had been commonplace since before the turn of the century but in Britain it was actively discouraged. In 1906 Hugh Locke-King had attended both the Italian Targa Florio and the French Grand Prix, both run on public roads with not a single British car to be seen. The speed limit which on Britain's roads was 20 miles per hour was to remain in force until 1930. British car makers obviously had no chance at all of competing in Europe on equal terms and it was obvious to Hugh Locke-King that an English off-road track and testing ground was sorely needed. In consequence he convened a meeting of like-minded motoring enthusiasts in Weybridge in September 1906. Present were the men who were to play a crucial part in the early days of British motor sport. Mr. E. de Rodakowski, who was to become Clerk of the Course at Brooklands opened the meeting and outlined the plans.

Experienced race driver and car dealer, 29 year old Charles Jarrott suggested a very large high speed track. Selwyn Edge, whose London based Motor Power Company held the agency for Napier cars, was keen that the cars should be visible to the spectators for as much of the circuit as possible. The conclusion was that the track would have to be banked, 100 feet wide and nearly 30 feet high in places.

To end on a high note, Selwyn Edge surprised everybody by announcing that he intended to book the track for an attempt to drive a Napier unaided at sixty miles per hour for an entire day and night - twenty four hours. A feat that was thought absolutely impossible, medical opinion at the time being that he would "lose his reason after eighteen hours".

The outcome of the meeting was that Hugh Locke-King was to spend over £150,000 building Brooklands and Selwyn Edge was to later attempt and achieve his 24 hour record.

Hugh Locke-King hired a man from the Royal Engineers, Colonel Holden to draw up the plans and a skilled railway engineer, John Donaldson to supervise the construction.

For nine months over seven hundred men worked almost around the clock for seven days a week, the only breaks being on Saturday and Sunday nights. The river Wey was diverted, smallholders were re-housed, thirty acres of woodland were felled and 350,000 cubic yards of earth were moved. Seven miles of rail track was laid and 200,000 tons of gravel and cement were brought in and cast to become the race track.

As well as the outer circuit, a finishing straight ran from the reverse curve section known as the fork to the member's banking making the overall track length 3.25 miles (5.23 km) of which two miles were level, the remainder being banked.

Chalk was brought from Reigate to build up the banking and workmen were drafted in from far and wide to swell the number of men on the site to over two thousand.

Ten steam grabs, countless traction engines and a dozen steam navvies dug away earth here and banked it up there to gradually create the banked sections. Because the centre of the site was swampy it had to be built up by five feet to form the finishing straight for a kilometre and a further acre also raised to the same height to form the site for the clubhouse, the paddock and the surrounding sheds.

During the excavations 1,600 year old Roman coins and urns were unearthed thus proving that the Romans had indeed formed a settlement at Brooklands.

The top layer of the track was originally to be tarmac but ultimately a six inch thick layer of gravel and Portland cement was laid. Asphalt could only be laid on concrete and so would have been too expensive and tarmac would have had to be rolled. This of course was a near impossibility on the steep banked sections, so the final decision was to use concrete which could be laid in shuttered sections from the bottom of the banked sections upwards.

Today if you take a short walk from the clubhouse to the member's banking you will see how well this has survived in nearly ninety years of use and abuse. Bumpy because the ballast underneath has settled but largely still intact at the surface. The track surface although damaged during the first war by military vehicles was repaired afterwards but never really recovered and by the thirties was heartily disliked for its bumpiness by many drivers including the Great Tim Birkin who voiced his disapproval in his autobiography Full Throttle. The second war saw major destruction as part of the banking was demolished and trees were planted through the concrete as camouflage against enemy aircraft which could pick out the track from over sixty miles away.

Even in 1906 there were many trucks on the English roads but despite this horses were used to do the pulling work at Brooklands. Perhaps this is not so surprising if you consider that when the first world war broke out seven years later, battles were still traditionally being fought on horseback and it had only been three years earlier, on the 17th December 1903 at Kittyhawk, that Orville Wright had become the first man to fly a powered aeroplane for a brief twelve seconds.

At first the workmen lived in chicken huts with fir branches for the roofs but then the medical health officer arrived on the scene and decreed that a large wooden hut had to be built for use as a dormitory. As well as the road builders, two hundred carpenters were employed to build spectator stands and seating for 5,000 people and to erect fencing and sentry boxes each of which was spaced at 300 yard intervals around the track. In all, the area occupied was almost 340 acres with a spectator capacity of 250,000.

The Grand Opening

On Monday June 17th 1907 the track was officially opened with an informal lunch party in the clubhouse for the various motor and horse racing leading lights of the time, with many of the press in attendance. A long procession of road and racing cars left the clubhouse for an initial tour of the track headed by Ethel Locke-King in her Itala after which one make groups of cars went out to be followed by the sight of a Darracq which ran high up the banking achieving a top speed of about 90 mph! Yes, it is true - 90 mph in 1907 while just over the fence the speed limit was 20 mph.