| MISSION COST AND RELIABILITY

Spacecraft production and operation are very expensive with typical program costs amounting to hundreds of millions of pounds. Mission costs may be divided into three main phases, each contributing a significant proportion of the total: the design and construction of the spacecraft, the launcher and launch program costs, and the cost of operations over the spacecraft life.

The main driving factor is the cost of spacecraft launch. Launchers are extremely expensive to build and use. A guided rocket, capable of delivering a spacecraft into orbit is an extremely large, complex, multi-stage device, subject to an extreme range of temperatures and burning highly corrosive and hazardous fuels. Guidance is complex, the launcher providing huge amounts of thrust in one axis, while also controlling the other axes to direct the rocket into the correct orbit. Launch opportunities are often limited by season or by the need to clear the vicinity of the rocket launch site and flight path. Launchers must be designed to be as highly reliable as possible. In the event of failure, even if another spare spacecraft exists, another launch opportunity may not exist for months or years. Despite this, launch failures are surprisingly common: 8% of all spacecraft fail to start operations (and 11% of those destined for high orbit). Current launch insurance policies cost about 13B17% of the spacecraft replacement value and relaunch. While competition for business between launch-vehicle consortia is fierce, with European, Japanese, Russian, Chinese and American launchers all competing for business, no one has yet been able to improve significantly launch reliability, reduce launcher cost and offer a rapid service. Russian and Chinese systems are less expensive than their western counterparts (Chinese rockets quoted as 30% cheaper), but their reliability and orbital injection precision has been questioned. Arianespace’s Ariane 4 launcher now receives favourable insurance treatment because of its 90.1% success rate, but has only managed a maximum of 8 launches in one year. The same companies recent launch failure on the maiden flight of the new Ariane 5 rocket, only illustrates the difficulties of making vehicles reliable.

The cost of the launch has implications for the design of the spacecraft. With the exception of communications missions requiring constellations of spacecraft, missions (and in particular, science missions) tend to be unique—a single spacecraft being launched to carry out a particular experiment or task, with no spare or alternative mission to carry out the same task in case of failure. If a spacecraft fails then the mission is unlikely to be repeated for years, if ever. Spacecraft must therefore be highly reliable, first surviving the harsh vibration environment of launch, and then operating successfully for long lifetimes without servicing and despite large radiation doses. The design and manufacturing processes must be rigorous, ensuring the correct operation of the spacecraft the first and only time it will be used. The systems and electronics are analysed down to a component level to ensure that the failure of any particular constituent part will not jeopardise the longevity of the whole mission. Design concepts must also be continually re-examined to verify their validity. Construction is to the highest quality with no expense spared.

The current design trend is towards simple, well-tested, conservative design, producing large, heavy systems that ignore new technologies. This further spirals mission costs—the size and cost of the launcher being proportional to the size and mass of the spacecraft.

High spacecraft and launch costs also affect the cost of mission operations. Support teams monitor spacecraft around the clock, to ensure continuing operation. At the first signs of failure, a network of experts is assembled to ensure that the best expertise is available to deal with ensuing problems. During normal operation, commands and instructions are carefully vetted to ensure that they do not jeopardise the spacecraft’s performance, before they are communicated to the spacecraft. Every aspect of the spacecraft operation is documented in minute detail, producing hundreds of volumes of technical manuals that describe courses of action for all considered eventualities. Communication with spacecraft is maintained during most phases of operation often as a matter of course. For non-earth orbiting spacecraft this is particularly expensive, requiring the use of large antennae in strategic locations around the world.

All of these contributing factors drive the costs of space programs into many millions of US dollars. Mission costs can be broadly estimated from the mass of the spacecraft (Figure 1-1), small spacecraft (around 1000 kg) costing hundreds of millions of dollars and large spacecraft (around 10000 kg) costing billions (Data from Jane's Space Directory). With such large programs, management is extremely complex, and there is a tendency for costs to spiral. Mission failures and cost over-runs are embarrassing for the organisations involved.

Recently, there has been considerable political pressure to reduce or to cap program costs, shifting emphasis from scientific ideals to science value-for-money. A budding micro-satellite industry offers budget priced access to space, providing a radical alternative to conventional spacecraft development programmes, but is only suitable for missions with modest objectives. NASA administrator Daniel Goldin announced his vision of "Faster, Better, Cheaper" conventional missions, which led to NASA’s Discovery Program intended to "accomplish high quality, focused planetary science, with innovative, streamlined, and efficient management approaches". The approach limits design and manufacture to 18 months, with operations limited to three years. Mission costs are capped to $185 million (fiscal year 1992).

Such new approaches to spacecraft design require new technologies to drive costs down while still producing more reliable spacecraft. New techniques are needed to guard against system failure. Increased spacecraft autonomy is required to allow the scaling down of ground activity and hence the reduction of mission support costs. Spacecraft must make better use of fewer, lower quality instruments and sensors to make them lighter and cheaper. NASA’s lead has sparked a general trend towards smaller, more advanced spacecraft for science and technology missions that require less expensive launch vehicles.

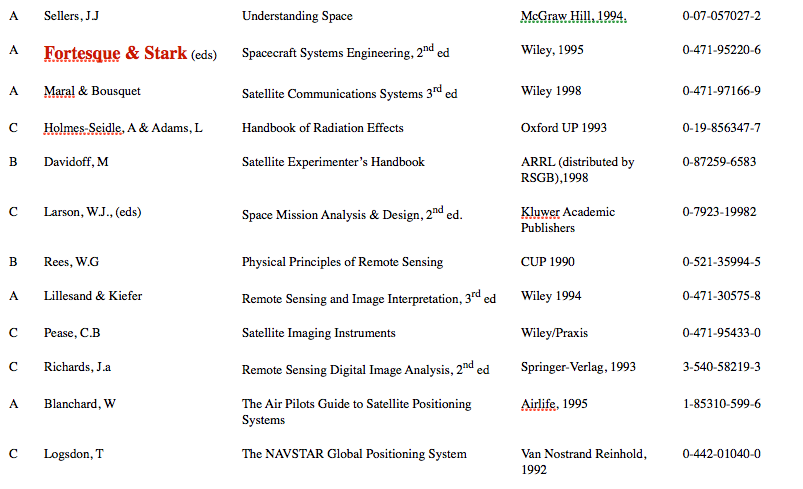

References

| Moss J. B., "Launch Vehicles", Spacecraft Systems Engineering, 2nd Edition, ed. | P. Fortescue and J. Stark, pp 145, John Wiley, 1995, ISBN 0-471-952206.

The Space review, Airclaims, June 1992.

|

"Long March Crash to End Insurance Discounts", Interspace, European Satellite and Space News Ltd, pp 1 & 4, 21 February 1996.

|

Wilson A., "Launchers", Jane’s Space Directory, 11th Edition, Jane’s Information Group Ltd, 1995, ISBN 0-7106-12591.

|

| Fortescue P. | and Stark J., Failures, Spacecraft Systems Engineering, 1st Edition, pp 396-397, John Wiley, 1991, ISBN 0-471-927945.

| Fortescue P. | and Stark J., Spacecraft Systems Engineering, 1st Edition, pp 6, John Wiley, 1991, ISBN 0-471-927945.

| The Discovery Project Statement of Objectives, NASA policy statement, NASA, http://www.nasa.gov, 1992. |

ERR050 Rymdteknik

(2,5 poäng)

(Space Techniques)

0741 - Radio- och rymdvetenskap

Examinator: Susanne Aalto Bergman

Rymdteknik är ett område med snabbt växande betydelse för Sverige liksom internationellt. Det är därför viktigt att vara medveten om problem och principer för rymdvetenskap och rymdteknik.

KURSENS SYFTE

Avsikten med kursen är att introducera några av de grundläggande aspekterna på rymdteknik, från en elektroteknisk synvinkel. Kursen är delvis översiktlig samtidigt som vissa problem av grundläggande intresse får en fördjupad analys. Tillämpningar kommer att ges utgående bl. a. från aktuella ESA-projekt. Kursen kan följas av teknologer i 3:e året. För vidare analys hänvisas t ex till ERR060 Satellite links, ERR011 Radar och fjärranalys .

KURSENS INNEHÅLL OCH ORGANISATION

Rymdhistorik, Sveriges roll i rymden. Satellitens omgivning: vakuum, tyngdlöshet, jordens atmosfär och jonosfär, geomagnetism, strålningsbälten, mikrometeorider och rymdskrot, solstrålning och solvind. Satellitbanor: Keplers lagar, banstörningar och korrektion av dem, geostationära banan. Satellitens läge på himlen. Raketer och raketuppskjutning. Satellitkonstruktion: materialval, energikällor, temperaturreglering, attityd- och banreglering, telemetri, telekommando och baninmätning, tillförlitlighetsaspekter, rymdkvalifikation. Satellitkommunikation: antenner, mottagare, bruskällor, länk-beräkningar.

Satellittillämpningar: Fjärranalys, navigering, astronomi, aeronomi, materialvetenskap.

I kursen ingår en obligatorisk inlämningsuppgift som utföres med hjälp av dator.

KURSLITTERATUR

P. Fortescue & J. Stark (red.): Spacecraft Systems Engineering, Wiley, 1995.

EXAMINATION

Skriftlig tentamen.

AAE 490E Course Details

Prerequisites:

| ECE 201 and Junior-level standing |

Text/Notes:

| Fortesque and Stark, Spacecraft Systems Engineering, Wiley Publishing Co., 1995. |

| The course will stress course notes, so good class attendance practices are strongly encouraged. |

Homework:

| Assignments handed out each week (approximately) and due one week later at the beginning of class. |

| NO late assignments will be accepted for any reason. |

| Collaboration on assignments is encouraged assuming the final product is distinct. |

Satellite of the Week:

| Groups of 3-4 students will provide 20 minute presentation on selected satellites (more detailed description to follow) |

Exams:

| Two exams will be scheduled during the semester. |

| A comprehensive final will be given during the scheduled time. |

Course Grade:

Homework

Satellite of the Week Lecture

Mid-semester Exams

Final Exam

20%

10%

40%

30%

|

|

![]()

![]()