Francis Alexander Fortescue Major

Arm ring of an African leader. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/arm-ring-of-an-african-leader/

Solid bronze arm ring, about 1850. Museum no. 254-1898

This bronze arm ring was originally amongst the possessions of a southern African leader. A letter pasted into the Victoria and Albert Museum's accession register reveals how it made its way into the collection. The letter reads:

'69 Eaton Terrace / Jan. 18 1898 / Dear Mr Clarke, I am sending by the bearer who brings this a small parcel, containing a bangle, the history of which is that it was taken off the skeleton of Moselekatze (I think that is how the name is spelt) when his grave was opened. Some buttons which were recently exhibited in the Museum of Bulawayo were found at the same time. The bangle contains a certain percentage of gold and I was told resembled the metal used for ornaments by the Phoenicians; of this you will be a better judge than I am. I can vouch for the authenticity of the bangle as it was given me when I was at Bulawayo in [18]96 by the man who opened the grave. I shall be very glad to give it to the Museum, if you consider it worthy. / Yours truly, F.A. Fortescue.'

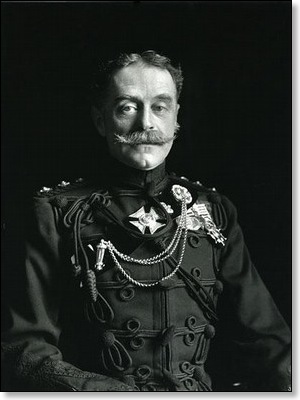

Portrait of Major Francis Alexander Fortescue, 1906,

Lafayette Portrait Studios, © V&A Images / Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Mzilikazi (also spelt Moselekatse) was born in what is now northern Zululand, South Africa, some time in the 1790s. He was the son of Mashobane, chief of a Khumalo subgroup. The period through which Mzilikazi lived witnessed great political and social upheaval in southern Africa. Drought, famine, the rise of military rulers and their kingdoms, and the invasion of European settlers and consequent slave-trading prompted the movement of people around the region on a large scale. Mzilikazi and the Ndebele 1 nation he founded were one of the products of this migratory era.

Mzilikazi's early military career was spent commanding a Khumalo regiment for the famous Zulu ruler Shaka. Around 1820 Mzilikazi rebelled against Shaka's authority and escaped with a few hundred followers. They first trekked across the Vaal River into what is now the northern part of South Africa before continued enemy attacks pushed them south west, to establish themselves on the Transvaal. They moved north again in 1827, to an area above the Magaliesberg mountain range, near modern Pretoria. Here Mzilikazi and his followers founded a settlement called Mhlahlandlela.

In 1838 the group moved northwards again into present-day Zimbabwe where they carved out an area which is now called Matabeleland in the west and south west of the country (Bulawayo is its major city). Here Mzilikazi founded his last settlement, also called Mhlahlandlela. While his journey had begun with a few hundred followers, under Mzilikazi's leadership the group's numbers had risen to, at their peak, some 20,000 people as conquered peoples were absorbed. Mzilikazi's greatest success was infusing his diverse population with a sense of common nationhood, one shared by the Ndebele community today.

Mzilikazi died in 1868 following a period of ill health. According to custom his death was kept secret for a period of time. His body was then placed in a wagon and, with a second wagon loaded with his possessions, taken to a hill named Entumbane in the Matopo Hills. Mzilikazi's body was placed inside a granite-walled cave which was sealed with stones. His possessions, which included clothes; utensils; sleeping mats; beads; ornaments and brass rings such as this arm ring, were placed in another cave with the wagon which had transported them.

William Cornwallis Harris, 'Mzilikazi (Moselekatse),

King of the Matabele' (detail), October 1836, image courtesy of Simon Keynes

During the period of his reign, Mzilikazi had regularly encountered Europeans, including Captain William Cornwallis Harris who made this sketch of him on the right. Mzilikazi tolerated missionary activity within Ndebele territory, largely as he viewed missionaries as a means by which he might gain access to European goods such as guns and horses. However, his relationship with other Europeans was less cordial. One of the reasons for Ndebele movement was violent clashes with the Boers, descendants of the first Dutch settlers at the Cape. Many Boer families had become frustrated with the British administration which ruled the Cape Colony and left in search of new lands. Their searches frequently brought them into conflict with local African rulers like Mzilikazi.

Following Mzilikazi's death, his son Lobengula (ca.1845-ca.1894) assumed power. In 1888 the mining magnate and politician Cecil Rhodes negotiated a land treaty with Lobengula. Known as the Rudd Concession, the treaty permitted British mining and colonisation of Matabele lands between the Limpopo and Zambezi rivers. As part of the agreement, the British agreed to pay Lobengula 100 pounds a month, as well as 1,000 rifles, 10,000 rounds of ammunition, and a riverboat. However it soon became clear that the treaty was part of a British strategy to take control of the region. The British South Africa Company established by Rhodes in 1889 set up its own government and made its own laws, as well as seeking more mineral rights and territorial concessions. The outcome of these colonial activities was the First Matabele War in which some 1,700 soldiers from Lobengula's most battle-hardened regiments were decimated by British firepower. The Company then carved out a territory called Zambezi, and later, Rhodesia, which now covers the area now occupied by the republics of Zambia and Zimbabwe.

In 1896 the Ndebele rebelled again in the Second Matabele War (celebrated in Zimbabwe as the First Chimurenga or War of Independence). It was this conflict which drew Major Francis Alexander Fortescue (1858-1942), the donor of the arm ring, to the area. Fortescue was a professional soldier who served in India, Afghanistan, Egypt and South Africa. He was posted to the latter on at least four occasions; in 1881, 1896, 1899-1900 and 1908-10. As he tells us in his letter, it was in 1896 that he acquired the arm ring. It is unclear why Mzilikazi's grave, which remains within the large granite outcrops of the Matopo Hills, was opened. Today the hills continue to be a place of great spiritual significance to the Ndebele community and were designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2003. Fortescue also collected other items made by Zulu-speaking peoples, largely beadwork. These he donated to the Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter, in 1935.

References

1. Mzilikazi and his followers called themselves Zulu yet were known to others as 'Ndebele' or 'Matabele'. 'Ndebele' is an Anglicised form of the Nguni word 'Amandebele', which in turn derives from the Sotho word 'Matabele'. The original meaning of the word 'Matabele' is unclear but it may have been used by Sotho speakers to mean 'strangers from the east'. Other intrusive groups in this period were given the same name by the Sotho.

Further reading

Becker, Peter. Path of Blood: The Rise and Conquests of Mzilikazi, Founder of the Matabele tribe of Southern Africa. London: Longmans, 1962

Kent Rasmmussen, R. Migrant Kingdom: Mzilikazi's Ndebele in South Africa. London: Rex Collings Ltd., 1978

Knight, Ian. Warrior chiefs of Southern Africa: Shaka of the Zulu, Moshoeshoe of the BaSotho, Mzilikazi of the Matabele, Maqoma of the Xhosa. Poole, Dorset: Firebird Books; New York, NY: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 1994